Is canola oil Bad for you? There’s so much conflicting information available online about seed oils. On the one hand, many health professionals and large associations such as the American Heart Association and the Heart and Stroke Foundation, recommend canola oil as a healthy option, touting its fat profile and cardiovascular benefits. On the other hand, wellness influencers claim that canola oil is toxic and blame it for our rising rates of chronic disease. This deep dive will walk you through the research on canola oil and its effects on health, empowering you to make an educated choice.

Source: Canola Council of Canada

Hello, readers! A quick note before you move on: a version of this post was originally published in my weekly newsletter, The Grocery Edit, on Substack. If you enjoy this post, subscribe to my newsletter for weekly content just like this, straight to your inbox every Saturday morning.

Where does canola oil come from?

Canola oil comes from plants belonging to the Brassica napus B. rapa or B. juncea species. This plant is part of the Brassicaceae family, which also includes cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower. The oil itself comes from the plant seeds which are a rich source of monounsaturated fats, with oil making up 45% of the seed’s volume (1).

How is canola oil made?

There are seven steps in the production of canola oil:

- Harvesting: the canola plant is harvested and separated from other weeds or stems picked up during harvesting.

- Flaking: the seed is rolled into a flake so that the oil is to extracted more easily.

- Cooking: flakes are cooked in a series of drums to help break down the seed.

- Pressing: most of the oil is removed by pressing the flakes. Any remaining pieces of flake are then pressed into a cake.

- Solvent extraction: the cake is put into an extractor and combined with hexane, a solvent that removes the rest of the oil. Hexane is then removed from the canola oil and reused.

- A small percentage of canola oil is extracted from seeds without chemical solvents (hexane) or heat. These methods are called double press, expeller press, or cold-pressed.

- Refining: the oil may be refined to improve the colour, flavour, and stability. The oil is also sent through filters to remove any leftover particles.

- Steaming: the oil is steamed to remove unpleasant odours or compounds.

Source: Canola Council of Canada

The linoleic acid (omega-6) and inflammation hypothesis.

Linoleic acid is the most commonly consumed omega-6 fatty acid. While it is considered an essential fatty acid (one that we must obtain from our diet), our needs are easily met by foods. Our intake of linoleic acid has substantially increased over the past few decades, largely due to seed oils and their presence in processed foods.

Note: not all seed oils are high in omega-6. Canola oil, for example, contains 20% omega-6 (or 2.7 grams per tablespoon), compared to corn oil, which contains 53% omega-6 fatty acids.

The concern with linoleic acid is its potential role in inflammatory pathways. Simply put, linoleic acid can be converted into other polyunsaturated fats (PUFAs) in the body, including arachidonic acid (ARA). Subsequently, ARA can be converted into bioactive compounds called eicosanoids. Persistent production of excess eicosanoids can contribute to inflammation, a risk factor for many chronic diseases.

While linoleic acid is a precursor to ARA, we also get ARA directly from food sources in the diet. Meat, poultry, eggs, fish, and dairy are our most significant sources of ARA. This point is often missed in anti-seed oil rhetoric, but if we’re going to fully embrace the linoleic acid hypothesis, we can’t discount these sources as potentially contributing to the very same pathway.

High intake of linoleic acid is a plausible mechanism by which Western diets contribute to inflammation, but there is actually very little evidence to support this.

A systematic review included fifteen randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of dietary linoleic acid on markers of inflammation in healthy individuals. The review found no significant results in markers of inflammation, including c-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, and PAI-1. Note: there were several limitations to this review, including the fact that many of the studies used were small, and some had inconsistent methods and reporting. Additionally, isolating the effects of a single fatty acid is difficult due to variability among other dietary components.

While this is not enough evidence to dismiss this hypothesis entirely, we certainly don’t have sufficient evidence to support it.

Clinical trials generally show that canola oil consumption reduces cholesterol and has a neutral or beneficial effect on inflammatory markers.

For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis included 42 studies that investigated the effects of canola oil on inflammatory markers and cholesterol levels. Results from the meta-analysis of the studies comparing canola oil against other edible oils found that canola oil significantly reduced total cholesterol, LDL, LDL/HDL, TC/HDL, Apo B, and Apo B/Apo A-1 compared to all other edible oils. The review found that consumption of canola oil up to 15% of total caloric intake led to a maximum reduction in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL. In all study categories, no difference in CRP was observed.

Another systematic review and meta-analysis included 27 randomized controlled trials looking at the effects of canola oil on blood lipids. The review found that canola oil was associated with a reduction of total cholesterol and LDL compared to sunflower oil and saturated fats.

A recent randomized controlled trial investigated the effects of canola oil and sunflower oil on oxidative stress and inflammatory markers. Participants used either 20 ml of canola oil or sunflower oil to replace their usual cooking oil over a period of 12 weeks (the most habitually used cooking oil at baseline was olive oil). At baseline, no groups were found to have elevated oxidative stress or inflammatory markers, and no changes were seen after the oil intervention.

Another randomized controlled trial investigated the effects of canola oil, olive oil, and sunflower oil on insulin resistance, inflammation, and oxidative stress in women with type 2 diabetes. Seventy-seven participants completed the study and were given either 30g of canola oil, olive oil, or sunflower oil to consume in addition to their balanced diet for 8 weeks. No significant differences in fasting blood sugar, insulin levels, or malondialdehyde (a marker for oxidative stress) were found between the three groups. However, the olive and canola oil groups had significantly lower CRP levels at 8 weeks compared to baseline.

A recent randomized controlled trial investigated the effects of replacing ghee with canola oil on markers of fatty liver, lipids, and blood sugar over a 12-week intervention. Participants were consuming 3-5 servings (5g per serving) of ghee at baseline. The intervention group received canola oil in place of ghee, and the control group was instructed to maintain their usual ghee consumption. The intervention group (canola oil) experienced a significant reduction in grades of fatty liver compared to control (ghee). The canola oil group also experienced a significant reduction in total cholesterol, LDL, fasting blood sugars, and insulin levels.

Similar findings were also reported in a randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of canola oil and olive oil compared to sunflower oil on lipid profile and fatty liver in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Participants received 25g of either canola oil, olive oil, or sunflower oil daily for 10 weeks. After 10 weeks, the group receiving canola oil had a significant reduction in various cholesterol levels as well as fatty liver markers.

While each of these studies has limitations and not all can necessarily be generalized to the entire population, the evidence overwhelmingly and consistently shows that not only is canola oil not harmful, it’s likely beneficial for health.

If canola oil is truly toxic, populations that consume more canola oil should generally experience higher rates of chronic disease and be more likely to die than non-users.

But this isn’t the case.

A study identified and prospectively followed 521,120 participants aged 50–71 years from the National Institutes of Health-American Association of Retired Persons Diet and Health Study. Individual cooking oil/fat consumption was assessed using a validated food frequency questionnaire. After an average of 16 years of follow-up, butter and margarine consumption was strongly associated with higher all-cause mortality (hard margarine had a stronger association than soft). In contrast, intakes of canola oil and olive oil were both inversely associated with all-cause mortality. Every 1-tablespoon/day increment of butter or margarine consumption was related to 7% and 4% higher all-cause mortality, respectively. In contrast, each 1-tablespoon/day increment of canola oil or olive oil consumption was associated with a 2% and 3% reduction in all-cause mortality, respectively.

And have you heard about the Nordic diet?

A Nordic diet is similar to a Mediterranean diet as it is rich in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and fish and low in red meat, dairy, and processed foods. However, the Nordic diet differs from the Mediterranean diet in that canola oil is the primary source of added fats in the diet, instead of olive oil in the Mediterranean diet. The Nordic dietary pattern has not received as much attention in research compared to the Mediterranean diet, but research generally shows favourable effects of the Nordic pattern of eating related to the risk of chronic disease, despite canola oil being the primary added fat.

One trial looked at the effects of a “Healthy Nordic Diet” (whole-grain products, berries, fruits and vegetables, canola oil, three fish meals per week and low-fat dairy products, avoidance of sugar-sweetened products) compared to an average Nordic diet (higher in saturated fat) on lipids and inflammation in people with metabolic syndrome. Significant decreases in non-HDL cholesterol, and non-significant decreases in other cholesterol levels, Apo B and Apo A1 were observed in the healthy Nordic diet group compared with the control. In addition, the control group experienced an increase in inflammatory markers during the trial, while the healthy Nordic diet group did not.

Similar findings were observed in a RCT looking at the effects of a “Healthy Nordic Diet” (rich in high-fibre plant foods, fruits, berries, vegetables, whole grains, canola oil, nuts, fish and low-fat dairy products, but low in salt, added sugars and saturated fats) compared to a traditional Western diet. Participants assigned to the Nordic diet were provided with all foods during the trial. Researchers found that after the 6-week intervention, the Nordic diet group had significantly lower LDL, HDL, LDL/HDL compared with the typical diet.

Contrary to what grocery store influencers will tell you, canola oil isn’t inherently rancid. But the products you have in your home might be.

The processing that canola oil undergoes does not make it rancid. Instead, these processes help remove volatile compounds, resulting in a more stable product with a better shelf life and higher smoke point. However, all fats and oils oxidize over time. This degradation generates compounds known to cause off-odours and off-flavours and can reduce the nutritional quality of the oil.

Many factors influence how long an oil or fat remains fresh. One important factor is fatty acid composition. Unsaturated fats, specifically PUFAs, are more susceptible to oxidation than saturated fats. Processing methods, storage conditions, and the antioxidant content of the oils will also impact oxidation. One study looking at rice bran, corn, peanut, and canola oils found that the stability of the oils decreased by 30% after 12 months of storage. The oils with the highest PUFA content, in this case, grapeseed oil, tended to break down faster.

So while the types of fats in canola oil can oxidize faster than saturated fats, this doesn’t make canola oil rancid. The recommended shelf life of canola oil is one year from opening. Once open and exposed to oxygen, it will degrade much quicker. For this reason, it’s recommended that you purchase only an amount that you can use within 6 months to ensure the best quality.

When canola oil (or any fat) is used as an ingredient in processed food, the shelf life is less clear. Food processing methods, such as heating, as well as nutrient interactions within the food can cause fat oxidation to occur at a faster rate. So while the canola oil or canola oil-containing products aren’t inherently rancid, it’s worth doing a pantry review to clear out any old products you have lying around.

What about hexane?

Another concern with canola oil is that it is processed using a chemical solvent called hexane. However, the hexane used in canola oil processing is removed in a later processing step, so only trace residues remain in the final product. The maximum permitted amount of hexane allowed in vegetable oils in Canada is 10 parts per million (ppm) (to my knowledge, a maximum level doesn’t exist in the U. S). Hexane residues continue to break down after the oil has been produced, so the actual amount of hexane remaining in your cooking oil at home is difficult to estimate. This study found that canola oil contained 0.042 mg of hexane per kg of oil. I have also read estimates closer to 0.8 mg/kg of oil.

Some canola oil is produced without the use of chemical solvents. This is called cold-pressed and is less common than conventional canola oil.

The provisional (draft) minimal risk level for hexane is 0.1 mg/kg of body weight per day, which is 6.8 mg per day for a 150 lb person. To reach this amount of hexane from oil alone (assuming 0.8 mg/kg of hexane in the oil), this person would need to consume 8.5 kg of oil in a day.

So while the chemical processing step makes canola oil more refined and processed compared to alternatives such as olive oil, only trace amounts of hexane remain in the final oil product. These levels are well below risk thresholds, and based on the research cited above, they do not appear to translate to negative health effects.

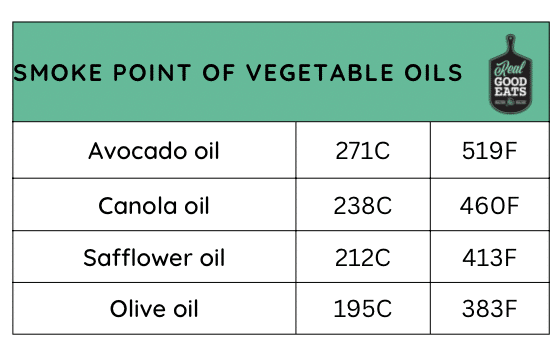

What is the smoke point of canola oil?

The smoke point of an oil is the temperature at which the oil will start to break down and potentially produce volatile compounds.

The smoke point of canola oil is 238C (460F), meaning it is safe for cooking up to this temperature. To compare this to other vegetable oils, the smoke point of extra virgin olive oil is 195C (383F), safflower oil is 212C (413F), and avocado oil is 271C (519F).

Canola oil is a source of oleic acid, which is more heat-stable than other unsaturated fatty acids. The heat stability makes canola oil a desirable choice for cooking. Another factor that increases the smoke point of an oil is its antioxidant content. Canola oil is generally rich in antioxidants, even more so when produced using cold-press methods.

Where do we go from here?

Canola oil is an easy target, and the claim that it’s harmful is easy to sell. After all, there’s a plausible mechanism of action, it’s found in many unhealthy foods and was originally called rapeseed oil for goodness’ sake. However, based on the available research, canola oil itself isn’t to blame. At best, canola oil seems to have a protective effect on chronic disease risk and inflammation; at worst, the effect is neutral.

Canola oil as a cooking oil.

Canola oil isn’t harmful, but whether canola oil is superior to other (unsaturated) cooking oils remains unclear. Current research supports public health recommendations to use oils rich in unsaturated fats. Whether this is canola, olive, or avocado oil, is a personal choice. While canola oil is an affordable cooking oil that offers health benefits, olive and avocado oil are less refined and processed without chemical solvents (though this extra step doesn’t appear to negatively affect health).

There’s also an argument for variety. Incorporating different fat sources in your diet can help avoid getting too much of an otherwise good thing. If the food system is already rich in canola oil and other seed oils (which is more or less out of your control), using alternative oils such as olive and avocado at home can help maintain a healthy variety of fatty acids in your diet.

Canola oil in processed foods.

It’s important to note that much of the available research uses canola oil as an added oil, rather than an ingredient in processed foods. There’s still reason to reduce our intake of ultra-processed foods, but not because they contain canola oil.

A processed food isn’t inherently unhealthy just because it contains canola oil, and there’s no reason to fear or avoid an otherwise nutritious food item simply because it contains canola oil in the ingredient list.

This post was originally published in my weekly newsletter, The Grocery Edit, on Substack. If you enjoy this post, subscribe to my newsletter for weekly content just like this, straight to your inbox every Saturday morning. You can also view a full list of sources in the original Substack post here.