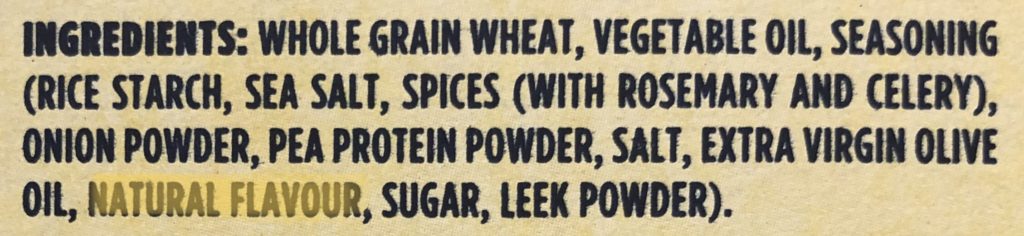

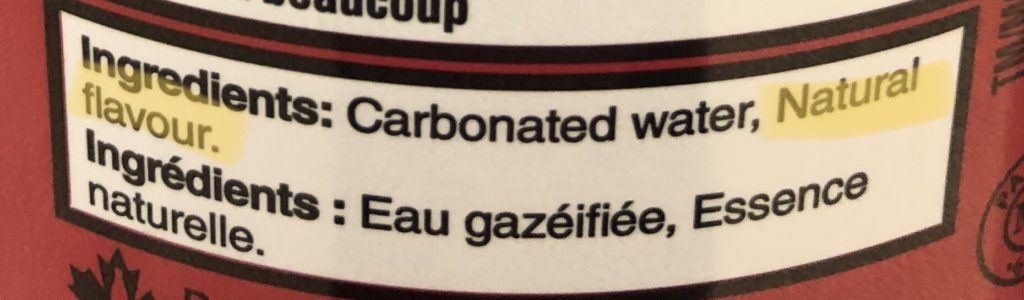

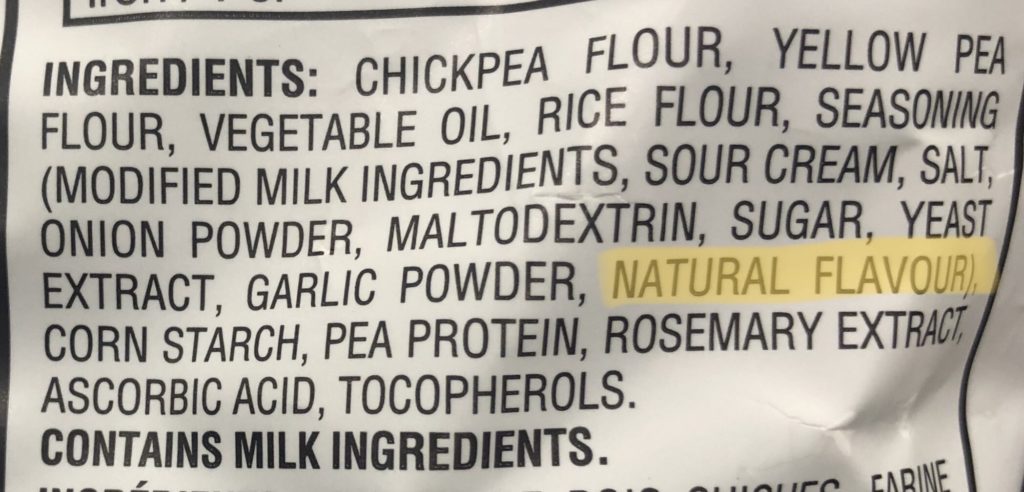

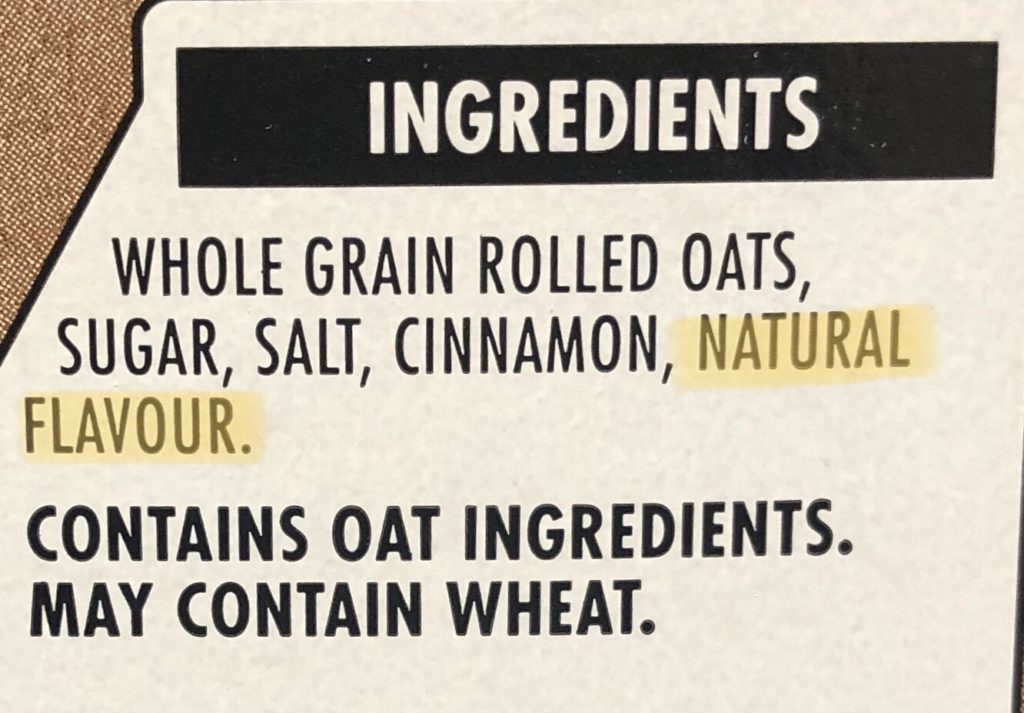

If you read food labels, you’ve probably noticed natural flavours on ingredient lists. And if you spend time on social media, you’ve probably heard that natural flavours are hidden sources of chemicals in food and should be avoided. It seems like this ingredient is in EVERYTHING, but what exactly is it? I’m sharing what you need to know right here.

Hello, readers! A quick note before you move on: this post was originally published in my weekly newsletter, The Grocery Edit, on Substack. If you enjoy this post, subscribe to my newsletter for weekly content just like this, straight to your inbox every Saturday morning.

First, let’s start with the basic definition of natural flavours.

The term “natural flavours” encompasses a wide variety of ingredients. These ingredients are regulated, meaning that food companies must follow specific criteria to use this term in the ingredient list.

The FDA defines natural flavours as follows:

The term natural flavor or natural flavoring means the essential oil, oleoresin, essence or extractive, protein hydrolysate, distillate, or any product of roasting, heating or enzymolysis, which contains the flavoring constituents derived from a spice, fruit or fruit juice, vegetable or vegetable juice, edible yeast, herb, bark, bud, root, leaf or similar plant material, meat, seafood, poultry, eggs, dairy products, or fermentation products thereof, whose significant function in food is flavoring rather than nutritional.

Basically, for an ingredient to be called a natural flavour, it needs to have the following components:

- Originate from a natural source (plant or animal product).

- Be extracted from one of the above sources via roasting (baking), heating (cooking), enzymolysis (breaking down an ingredient with enzymes), distilling (to create a liquid, concentrated vapour), or protein hydrolysate (breaking protein into smaller peptides).

- Provide flavouring only. A natural flavour cannot provide any nutritional value to the food or make any changes to the food other than flavouring (for example, a natural flavour cannot also add colour to the food).

At a high level, here are some examples of what can be classified as a natural flavour:

- vanilla extract

- essential oils from citrus fruit

- garlic extract

- onion juice

But the term “natural flavour” can only be used if it originates from the flavour that is simulated.

If none of the natural flavor used in food is taken from the food that the flavor is simulating, this is not considered a natural flavor. Instead, the specific ingredient must be listed, or the term artificial flavor must be used.

For example, if a protein bar called “Vanilla Protein Punch” contains vanilla extract, this can be listed under the term “natural flavours”. But if that same protein bar contains blueberry extract, the product must specify blueberry extract as an ingredient, or use the term “artificial flavour”.

There are many legitimate reasons why a company may choose (or be required) to use the term “natural flavours”.

First, the food you’re looking at is likely shelf-stable. Adding fresh ingredients, such as a squeeze of fresh lemon, directly into a shelf-stable food is often impossible due to the limited shelf life of fresh ingredients. For this reason, lemon essences processed from lemons will be added instead.

Another reason is that flavour profiles are complex. For example, a lemon has more than 30 components that make up the aroma we recognize as lemon (α-terpinene, α-pinene, limonene, sabinene, β-pinene, to name a few). A company may use the general term “natural flavours” in reference to these components, rather than citing the individual compounds used in the product.

Lastly, and perhaps the most important, the recipe for a food product is proprietary. Product development is expensive, and the intellectual property of flavouring formulas and product recipes is often the most significant asset of a food company. One way of protecting this asset is by using the term “natural flavours” rather than disclosing the exact ingredients used to develop the flavour profile.

Regulations also exist that require foods to use the term “natural flavour” rather than the actual ingredient name:

If a food is expected to contain a specific ingredient, and the food contatins natural flavor from that ingredient in an amount that is insignificant, or the food is flavored without the use of this actual ingredient, the term natural flavor must be used.

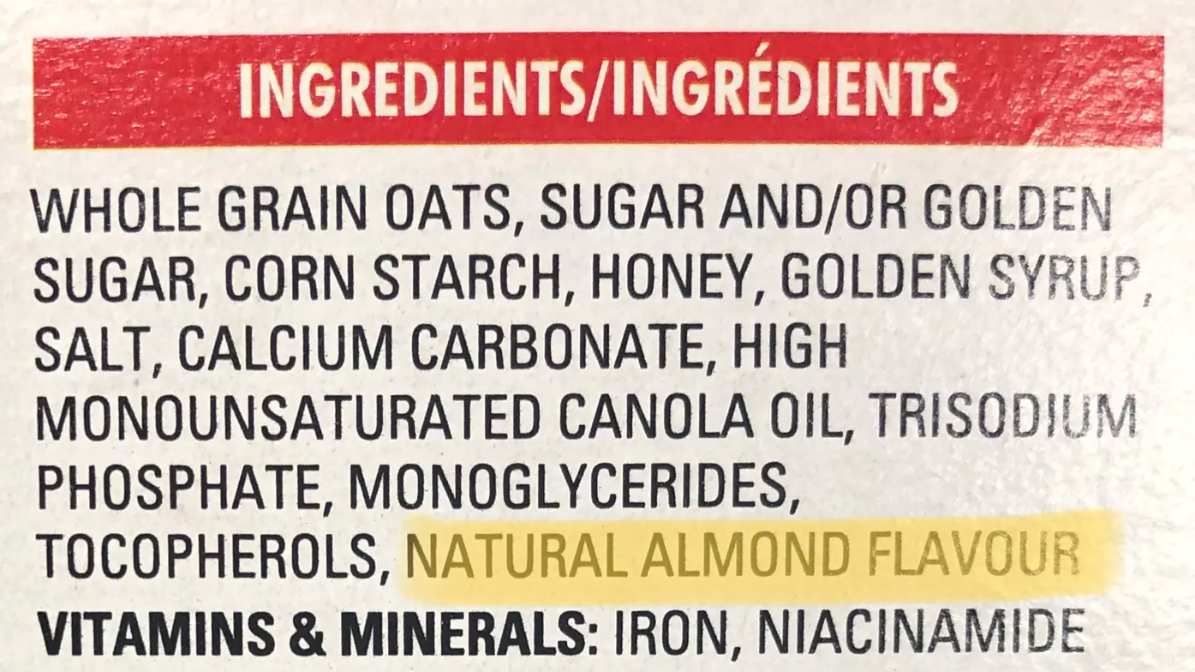

For example, in a cereal called “Blueberry O’s”, we expect to see blueberry in the ingredient list. But if the blueberry O’s are flavoured with a minuscule amount of blueberry extract and no actual blueberries have been used in the cereal, the company must use natural flavours instead of blueberries in the ingredient list.

Priority allergens in natural flavours must be disclosed.

In Canada and the U. S., priority allergens must be declared on a food label if they are an ingredient or part of an ingredient complex. If a natural flavour contains a priority allergen, this needs to be identified on the food label as part of the allergen statement. Typically, this will appear in the “contains” statement at the bottom of the ingredient list.

Natural flavours are made up of chemicals, but not necessarily in the way that you think.

You may have heard that natural flavours are just a way for food companies to hide chemicals in our food. Let’s break this down. There are two categories of “chemicals” that are possible in natural flavours.

First, natural flavours are made up of chemicals, but in the same way that everything is made from chemicals, even H₂O (water).

For example, ethyl 2-methyl propanoate, ethyl butanoate, and ethyl 2-methyl butanoate are fruity aroma esters in oranges. When you break food down to a micro level, everything is chemistry. Again, adding fresh ingredients to shelf-stable food isn’t always possible. And even fresh ingredients would have chemical names if we looked at their most basic form.

But natural flavours may also contain synthetic ingredients.

This is the second category of “chemicals”. While the source of natural flavours must be natural, there is some grey area in what can be added during the development of flavour complexes.

Non-natural carriers can be used [in the production of natural flavors] but only if they do not react irreversibly and do not serve as a substrate. Carriers may remain in the final mixture provided they are permitted as carrier solvents for natural flavorings.

Certain synthetic substances have been approved for use in natural flavour complexes, but only to support the processing, not as a key ingredient in flavouring. These substances can remain in the final product, with certain limitations. This means, not all natural flavours are entirely natural.

For example, hexane is a chemical used in food manufacturing. It is commonly used in vegetable oil processing and is approved for flavour extraction from spices, including in natural flavours. Residues from hexane can remain in the final natural flavour complex, at a maximum of 25 ppm.

The exception here is in the case of organic products, which cannot contain natural flavours with synthetic ingredients:

For organic food, all flavor constituents of the natural flavor must be from natural sources that have not been chemically modified in a way that makes them different from their natural state. Additionally, the natural flavor cannot be produced using any synthetic solvent and carrier systems or any artificial preservatives.

The idea of synthetic ingredients in our foods is an increasing concern for consumers. And rightfully so. We have lost trust in the food industry, and there are a lot of loud voices right now demonizing foods on the basis of not being “natural”. While I won’t be detailing the safety of synthetic additives in today’s post (which deserves a deep dive on its own), there is some context here that I think is extremely important before we sound the alarm.

Synthetic ingredients used in natural flavours are regulated.

Food manufacturers can’t freely add a bunch of synthetic chemicals into food. Food additives and ingredients used during manufacturing, like hexane, are studied for safety. Minimum risk levels are established, and uncertainty factors are applied to ensure that levels in the food system fall well below any level that could potentially pose a risk to humans. In the case of natural flavours, regulations also exist surrounding how much of an additive can be present in a final flavouring complex.

Synthetic ingredients from natural flavours are present in virtually undetectable amounts in the final food product (if at all).

There’s an old saying, “The dose makes the poison”. This is true for everything, natural or synthetic. Any substance, even water or oxygen can be toxic if over-consumed. But when consumed in appropriate, typical amounts, the same substance can be completely safe, or in the case of water and oxygen, even essential to health.

Let’s look at how much synthetic residues we’re dealing with in the case of natural flavours. While some synthetic ingredients can be present in natural flavours, remember that not all natural flavours contain these ingredients. And those that do are allowed to contain only trace amounts.

For example, the amount of hexane allowed to remain in a natural flavour complex is 25 ppm (parts per million). This equals a maximum of 0.0025% of the natural flavour preparation.

To put this into context, the maximum amount of gluten allowed in a gluten-free food is 20 ppm (or 0.0020% of a food). This is considered a safe amount of gluten that is tolerated by most people with celiac disease (for whom gluten is harmful).

But we’re not eating a big ol’ bowl of natural flavours. We’re eating food that contains natural flavours in small amounts, typically 0.05 to 0.40 percent of the final product weight. This means that if a 24 g granola bar contains natural flavours with hexane residues, the natural flavour could provide a maximum of 0.0024 mg of hexane. The provisional (draft) minimal risk level for hexane is 0.1 mg/kg of body weight per day, which is 6.8 mg per day for a 150 lb person. This person would need to eat over 2,800 (!) granola bars in a day to reach the minimal risk level of hexane from natural flavours. The amount of synthetic ingredients we are talking about here is minuscule. To revisit the gluten analogy, if this were gluten, it would be 192 times lower than the safe amount allowed for someone with celiac disease.

You don’t need to avoid natural flavours because they may contain synthetic ingredients, but they shouldn’t necessarily be there to begin with.

Food labelling is complex. There are many regulations in place to maintain the safety and consistency of food products. When researching for this post, I couldn’t help but think about one labelling law in particular:

Claims related to the method of production are also subject to subsection 5(1) of the Food and Drugs Act and subsection 6(1) of the Safe Food for Canadians Act, which prohibit statements and claims that are false, misleading, deceptive or that create an erroneous impression regarding the product.

According to food labelling laws, products cannot use claims that are misleading to consumers—period. Many existing labelling laws are actually in place to prevent manufacturers from using deceptive or misleading language. For example, a product cannot claim to contain “100% real cheese”, if it’s not made with actual cheese. Why aren’t the same standards used in the case of natural flavours? From my perspective, listing ‘natural flavours’ on an ingredient list for a product when the natural flavours contain synthetic ingredients, even in small amounts, is misleading to consumers. This type of inconsistency only fuels the mistrust that consumers have with both the food industry and the laws that are in place to keep our food safe.

Natural flavours TL;DR

If some of your go-to packaged foods contain natural flavours and are otherwise nutritionally sound, enjoy them and don’t give it a second thought.

This post was originally published in my weekly newsletter, The Grocery Edit, on Substack. If you enjoy this post, subscribe to my newsletter for weekly content just like this, straight to your inbox every Saturday morning. You can also view a full list of sources in the original Substack post here.

Good info presented in an understandable fashion

This is reckless advice… “thousands of oils” was a term used to describe what is in “natural flavours”. If just one of those is a seed oil, it’s literally poisonous. Saying “it’s not something to be concerned about” is pathetic. You are a part of the problem, Brittany.

Jackson, an understanding of the chemical composition of whole foods is required here. To clarify, the comment you are referring to above reflects extracted components of foods, not ingredients. For example, a lemon has 30+ essential oils that make up the aroma we recognize as lemon (α-Thujene, α-Pinene, Camphene, Sabinene, β-Pinene, to name a few. THESE are the oils I am referring to in the point you have quoted. Any of these oils used can be classified under “natural flavours”. Your comment about seed oils is inaccurate – when added to a packaged food, these oils are listed as an ingredient (ex. under the general term vegetable oil or as individual oils – sunflower oil, corn oil, canola oil, etc.). These oils are not considered natural flavours.